Of the schools so far Spain’s scene is smaller or at least less known and so provided is this following disclaimer, the information provided can not be done so with the same confidence nor can it be inferred from the wealth of sources provided before. Interest in the Spanish Schools and reliable English translations are relatively new, making it an infant scene among modern researchers. Still, what is known and available has an interesting dynamic within Spain as the competition between schools was fierce. The main School was Destreza which might be contextually translated to The True Art and they looked down on the common fencing schools within the region.

Much like the Italian Schools who were spread out over multiple republics and even some kingdoms, the term Spanish school is actually technically incorrect as the schools were much more regional. For a brief window during the late medieval/renaissance period the entire peninsula was even under one crown. The various masters came from Spain and Portugal and they were much in dialogue with each other, and in competition.

-Political Map of Iberia 1570. Wikimedia Commons.

According to Mele, early records are “scant” and “focus entirely on mounted combat”. German and Italian sources featured mounted combat but much more rarely compared to combat on foot. One early source was Dom Duarte of Portugal written in 1423, the work was not a manual on fencing but instead on how a knight should train. Duarte’s second work was on horsemanship, jousting and some wrestling. This emphasis on mounted combat would continue with writers such as Ponc de Menaguerra of Valencia and Juan Quixada de Reayo.

When genuine fencing manuals arrived it was the sixteenth century and within Spain they seem to have had an immediate schism. As much as there was a shared tradition and language between Iberian fencers there was a volatile rivalry between the established La Verdadera Destreza (True Art/True Skill) started by Jerónimo carranza and the common fencers (esgrima común) who are thought to be vulgar swordsmen who had acquired bad habits from foreigners and whose work was not scientifically sound. To a Destreza practitioner the accepted science appeared to be grounded in a classical education particularly Aristotle’s cause and effect.

-Portrait of Carranza. De la Filosofia de las armas y d su Destreza (1582). Wikimedia Commons.

Destreza’s influence while mixed outside of Iberia was monolithic within the region and as a result of precious little is known about the ‘Common Fencer’. Sources such as Tomas Luis appear to offer an outsider’s perspective on Destreza and various fencing going on with Portugal at the time. A few plays particularly in later writers are implicitly labelled as a counter to the tactics of the common fencer, who usually appears as someone overly aggressive, hasty and who lunges in while adopting all manner of odd positions and guards, implied to be inefficient in movement. Recently there is an English translation of Domingo Luis Godinho by Tim Rivera. Domingo Luis Godinho was a Portuguese fencing master and contemporary of Carranza and is the only comprehensive source of Pre-Destreza Iberian fencing. The work itself is rather disorganised which is not unusual for an older manual though more so prompting speculation of it being an earlier draft. What is described within the manual appears to resemble the Italian fencing tradition if somewhat loosely. Like other traditions, both Italian and Iberian it favours the thrust though does advise on cuts, particularly as a tool for subjection which is common to both regions.

-Cover of the modern translation of Godinho’s Arte de Esgrima. Acquired from AGEA Website.

When Jerónimo carranza released his work “Philosophia de las armas y de su destreza” which may be translated to The Philosophy of Arms it was loaded with philosophy featuring many references to classical philosophers principally Aristotle. When it came to the swordsmanship like Agrippa in Italy there was an earnest attempt to lay out a system that was sound geometrically. The system was lauded within Iberia and even respected outside of the region and the respect for the tradition can be seen in that it survived for roughly two hundred years. Carranza himself was a noble and administrator with a high class education and so his work was well received among the Iberian (particularly Spanish) upper crust. Carranza’s work attempted to apply mathematics to the fencing similar to the Bolognese Masters but taking it further. The main defense was linked to the right angle and many manoeuvres and even the basic distancing and footwork revolved around a circle.

Following Carranza within the tradition would be Luis Pacheco de Narváez who mostly built off of Carranza’s work but attempt some deviations still he was a popular and respected fencer within his own right. While Pacheco was easily the second biggest name within La Verdadera Destreza his volatile personality at least in writing earned him a somewhat negative reputation. Early within his work The New Science he calls out the Italian tradition as a “deformed and horrendous monster that men have venerated”. He specifically names and shames various masters including Joachim Meyer. Some writers of Leichtenauer have called out “False-Masters” but Pacheco is particularly antagonistic. While an accomplished fencer his boasting may have set back Destreza’s reputation somewhat. This is possibly why when Egerton writes his history of fencing schools in the 19th century he is particularly dismissive of the Spanish school.

-Luis Pacheco de Narváez. Wikimedia Commons.

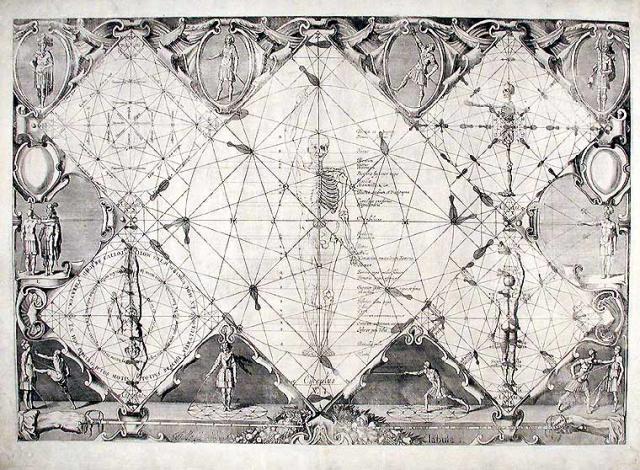

Destreza would have its fair share of masters and names and much of it is lost or not easily accessible but Francisco Lórenz de Rada and Don Francisco Antonio de Ettenhard have stood out as comprehensive and more succinct explanations of Destreza. Writing directly after Pacheco is Diogo Gomes de Figueiredo writing his Oplosophia which while covering conventional destreza also includes a wealth of companion weapons and even a fairly extensive montante/spadone (long two handed sword) section. More contentiously is the often included Gerard Thibault whose inclusion among Destreza masters is debatable. Certainly many considered him Destreza, including himself and he does apply many of the principles and lessons of Destreza to what he built. However, he is a Dutch man writing in Spanish Netherlands and he implements many Italian and French additions to his system making his work contrast with the earlier and more orthodox works. His book also frequently strays into the cosmic and esoteric. Still he was an accomplished master and is often associated with the tradition.

-Gerard Thibault’s Mysterious Circle. Unlike many other authors of Destreza Thibault’s work was immaculately illustrated. The circle is a recurring element within Destreza. Image is acquired from Wikimedia Commons.

Weapons involved in Destreza are diverse and they would explained it like other schools as being about principles rather than what weapon you are using. However the emphasis of destreza is predominately on the single sword, at the time a fashionable blade dubbed the Espada Ropera loosely meaning dress or court sword. This resembles the spada da lato of Italy and rappier of Germany. The art would eventually be dominated by what are sometimes colloquially referred to as late rapiers and they were infamously fond of the cup hilt which may have been more protective of the hand especially when held in an extended arm position. As mentioned, Masters like Figueiredo covered companion weapons these include items such as a dagger, buckler, rotella (a shield), cloak, vambrace (or armbrace) and bracer. The staff and montante were also covered by various masters, and Figueiredo’s montante section involves practical exercises such as clearing a street, escaping an alley or fighting on a galley, placing it in a similar context to Godinho’s two handed sword section.

There is a strong emphasis on keeping oneself at a defensive distance and not making uncompromising motions, that is to say balanced and non-committed footwork. The main defense within Destreza is the defense of the right angle or the right angle guard, this is to describe an upright posture with the arm extended so that the body is retracted from danger while arm remains at almost maximum extension. Footwork is explicitly non-linear as relating back to the circle one can strike their opponent by getting offline and do so more safely than if they had advanced linearly. The lunge is disavowed as something risky and unbalanced. Cuts are delivered with circular motions, either full or half to build up momentum and in response to the right pressure or action from the opponent, these cuts still being used when the Italians had to an extent disregarded them in favour of the thrust. More so than the difference between Italian and German traditions, Destreza’s principles and geometric focus made the Iberian schools stand out as something distinctly unique.

Bibliography:

- AGEA EDITORA. A very brief history of the Verdadeira Destreza in Portugal. Last accessed: 06/11/2017. http://ageaeditora.com/en/brevissima-historia-da-verdadeira-destreza-em-portugal/

- Blair, Charles. 2015. Que llaman estar nerbado: the Spanish response to the Italian fencing tradition, 1665–1714. Acta Periodica Duellatorum. 3(1): 63-100. Retrieved 4 Nov. 2017, from doi:10.1515/apd-2015-0003

- Blair, Charles. 2015. The Neapolitan School of Fencing: Its Origins and Early Characteristics. Acta Periodica Duellatorum. 2(1): 9-26. Retrieved 4 Nov. 2017, from doi:10.1515/apd-2015-0012

- Castle, Egerton, Schools and Masters of Fence, from the Middle Ages to the eighteenth century (York, Pa., G. Shumway, 1969).

- Curtis, Puck and Curtis, Mary. Destreza Translation and Research Project. Last accessed 22/09/2017, http://www.destreza.us/translations/ettenhard.html

- Diogo Gomes de Figueiredo. (Partially Translated. Lois Sprangler). Oplosophia e Verdadeira Destreza das Armas. (AEGA, 2013).

- Don Francisco Antonio de Ettenhard. (trans. Mary Curtis). Compendium of the Foundations of the True Art and Philosophy of Arms. Destreza Translation and Research Project. Last accessed: 06/11/2017.

- Gerard Thibault D’Anvers. (trans. Greer, John) The Academy of the Sword. (Aeon books, 2017).

- Jaquet, Daniel, Verelst, Karin and Dawson, Timothy (and others). “Late Medieval and Early modern Fight Books: Transmission and Tradition of Martial Arts in Europe (14th-17th centuries).” (2016, Leiden: Brill).

- Luis Pacheco de Narváez. (trans. Puck and Mary Curtis) Letter to the Duke of Cea. us. Last accessed: 06/11/2017. http://www.destreza.us/translations/narvaez_italian.html

- Luis Pacheco de Narvaez. (Trans. Mary Curtis, 2004) New Science. Destreza Translation and Research Project. 2004. Last accessed: 06/11/2017.

- Luís, Thomás. 1685. (Trans. Jaime Girona, Manual Ortiz, Thomás Ahola and Ton Puey). Tratado das licoes da espada preta. (AGeA, 2010)

- Mele, Gregory D. “Fighting Arts of the Later Middle Ages.” In Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation, edited by Thomas A. Green and Joseph R. Svinth, 242-248. Vol. 1, Regions and Individual Arts. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2010. Gale Virtual Reference Library (accessed October 30, 2017). http://go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=uq&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX1765500064&asid=28a55f4634a079daae5af8ce8dd22931.

- Mele, Gregory D. “Fighting Arts of the Renaissance.” Martial Arts of the World: An Encyclopedia of History and Innovation, edited by Thomas A. Green and Joseph R. Svinth, vol. 1: Regions and Individual Arts, ABC-CLIO, 2010, pp. 249-256. Gale Virtual Reference Library, go.galegroup.com.ezproxy.library.uq.edu.au/ps/i.do?p=GVRL&sw=w&u=uq&v=2.1&it=r&id=GALE%7CCX1765500065&asid=030c74c7d51f916a624f10143a79002b. Accessed 30 Oct. 2017.

- Ortiz, Manuel. “The Destreza Verdadera: A Global Phenomenon”. Late Medieval and Early Modern Fight Books. 2016, Leiden: Brill

- Pacheco de Narváez, Luis. Nueva ciencia y filosofía de la destreza de las armas, su teórica y práctica. Mary Dill Curtis. (Madrid: Melchor Sánchez, 1632).

- Price, Brian, and Stern, Laura. The Martial Arts of Medieval Europe, 2011, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

- Puey, Ton. An overview of the Iberian Montante. HROARR. 2015. Last accessed: 06/11/2017.

- Rivera, Tim. “Iberian Swordplay: Domingo Luis Godinho’s Art of Fencing 1599.” (2016, Freelance Academy Press, Inc).

- Rivera, Tim. Spanish Swordsmanship society of St. Louis. Last accessed 22/09/2017, https://www.spanishsword.org/translations

- Smith, Nicholas, and Zaphy, Jonathan. A Civil Death: The Civilianization of the Sword—honor, Reputation, and the Rapier, 2014, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses.

- Terminiello, Piermarco. Fencing culture, duelling and violence. HROARR, 2013. Last accessed: 04/11/2017. http://hroarr.com/fencing-culture-duelling-and-violence/

- Terminello, Piermarco and Reich, Steven. Florentines Doing “Florentine” Combat with Two Swords According to Francesco di Sandro Altoni (c.1540) and Marco Docciolini (1601). HROARR. Last accessed: 06/11/2017. http://hroarr.com/florentines-doing-florentine-combat-with-two-swords-according-to-altoni-and-docciolini/

- Terminiello, Piermarco. Giovanni Battista Gaiani (1619) – An Italian Perspective on competitive fencing. (2013) HROARR. Last accessed: 04/11/2017. http://hroarr.com/giovanni-battista-gaiani-1619-an-italian-perspective-on-competitive-fencing/

- A HEMA Alliance Project. Last accessed 22/09/2017, http://wiktenauer.com/