This was not made to with the intent of being public or on this blog, so if the translators and publishers of work featured here want this article taken down they can message me and it will be done.

Introduction:

My focus of study has been the Late German Rapier style as derived from Fabris (with some influence from Capoferro and Thibault).

I have from the beginning focused on the German lineage, and for rapier this has been my primary focus as well. I have been investigating this tradition for at least two years. Not all of it has been internalised or committed to memory but I have read 98% (super rough estimate) of the resources available on this style. The remaining books to read being Heussler, and the last quarter of Bruchius. Another remaining work to read is Wilhelm Kreußler’s treatise but there is no available English translation to my knowledge.

This document serves as a rough summary, trying to catch both what is fundamental and what is novel about this fencing system. In truth, little will look out of place to the Italian fencer, especially one familiar with Fabris. There are some stylistic differences, and as Reinier van Noort has pointed out the similarities, particularly in phrasing and structure place them in their own visible tradition.

Some passing mention will be made to other styles, but principally this document refers to Thrust-fencing (Stoß–fechten). Not all authors mention cut-fencing (hieb–fechten) or other forms of fencing but all named authors feature thrust-fencing.

Authors:

Disclaimer: I have lent my copies of Salvator Fabris and Johannes Georgius Bruchius’ work and so I cannot confirm details in them, I read them some time ago and am acting from memory. I do not own and have not read Wilhelm Kreußler’s treatise. I have only recently acquired Sebastian Heußler’s work and so have not read it.

The information on authors is taken from the manuscripts, the forewords/their translators, and Wiktenauer. If no citation provided should be assumed it is from those sources.

Salvator Fabris (1544-1618)

Salvator Fabris was a prolific Italian fencing master who published ‘Lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme’ in 1606 and represented two books. Book One resembles conventional Italian fencing, like say Capoferro, Giganti or Alfieri, Fabris dubbing this book firm-footed. Book two is the book that receives way more interest from modern practitioners due to its novel way of fencing, proceeding with revolution. Fabris taught not just in Italy but outside of it in Paris and (what was then) Germany. Throughout the 17th century he had his works copied and translated. Both books became highly influential in the area. He is often referenced by name, and sometimes plays and paragraphs seem copied, this is particularly the case with H.A.V. Fabris’ book included Rapier, Rapier and Dagger, Rapier and Cloak, and Grappling. He also has disarming actions and half-swording (referred to as two-handing). Fabris is mentioned here as he was essentially the progenitor of the tradition, directly or indirectly.

Sebastian Heußler (1581 to mid-late 17th century)

I cannot say much on Sebastian Heußler as I only just acquired his work. It appears to be a blend of Capoferro and Fabris and the plates certainly remind me of Giganti. The treatise Neu Kunstlich Fechtbuch (1615) looks quite extensive. Material covered by Heußler is Rapier, Rapier and Dagger, Rapier and Cloak, Dagger, and Flag-waving. I felt he deserved an honourable mention because he was one of the earlier names in the tradition and not a small or uninfluential treatise it seems.

Joachim Köppe (16th century to mid-17th century)

Joachim Köppe also spelt Köppen was a 17th century fencing Master. Köppe is mentioned as one of my main sources more out of affection than use. His rambling made reading his treatise more engaging and human, and his attempt to tell Thibault’s practitioners they did Spanish fencing wrong was humorous, as after dismissing it he even provided his own diagram to ‘correct’ them. His treatise ‘Newer Discůrs Von der Rittermeszigen und Weitberůmbten Kůnst des Fechtens’ was written in 1619. It was influential enough to be plagerised by Bruchius, who was then copied by Schmidt. He said he received Fabris’ book from his personally in Paris, and he spends some time arguing with a hypothetical practitioner of Thibault. He protests that his work is not copied from Fabris but written to reconcile the old tradition with the new. Of German Rapier authors, I read Köppe’s work entirely first and perhaps due to inexperience found it difficult to interpret, I always intended to give it a revisit to see if it would make more sense now. I do enjoy emulating his posture and regularly think back to his commentary on stance, moving and measure. Köppe’s book lays out an order of the art covered, seemingly by priority.

- Single Rapier, pede firmo (firm-footed).

- Single rapier per caminada (proceeding and passing).

- Rapier and dagger, pede firmo.

- Rapier and dagger, per caminada.

- Cut-fencing and longsword

- What you do when assaulted or ambushed.

- Half-staff. Commentary on long pike and Halberd.

- Grappling.

Despite these listings, the translation I have is only of a rapier treatise. Seemingly this translation is the pede firmo and per caminada sections. I am unsure if he ever finished writing these works, or if they were ever translated.

Johann Georg Pascha (1628-1678)

Johann Georg Pascha, also spelt Pasch, Paschen and Passchen was a prolific publisher of materials. Wiktenauer lists fifteen published works. Pascha’s works are interesting for a few ways. His early works were written without a familiarity with Fabris’ work but still show the influence Fabris has had on German fencing. It was clear that the tradition had already been exported to Germany and had become part of the scene. Pascha also attributes one of his works to H.A.V which is the most derivative work of Fabris in the German tradition. Reinier van Noort and Jan Schäfer both speculate on who is H.A.V, the leading guess being Heinrich von und zum Velde.[1] Pascha’s relevance to me is that he presents a very orderly treatise, that is a bit dry but still concise. This makes it easy to study and work from. His principles on thrust-fencing are laid out in five small pages (of the translation) and then the rest is practical lessons that repeat a little bit, adjusting similar plays for different footwork or actions. Pascha published material on Rapier, Pike, Musket, Flag, Partisan, Hunting-staff, vaulting and grappling. Much of this material seems to have been copied or adopted by Johann Andreas Schmidt, and by extension Jonas Thomsen von Wintzleben.

Jéann Daniel L’Ange (Late 17th century)

Almost certainly, Jéan Daniel L’Ange was not a French-men as his name implied. Reinier van Noort has delved into the family history to find a German fencing family of the surname Lange. In recognition of this Wiktenauer has rendered the name Johann Daniel Lange which is the German spelling of his name. L’Ange’s work was published in 1664 and titled Deutliche und gründliche Erklärung der adelichen und ritterlichen freyen Fecth-Kunst. What I personally appreciate about L’Ange is his book’s shortness. It is organised in how it is laid out, and it is easy to read, and never dwells on a subject or lesson for too long. He also has a very refined use of hand-parrying and a more extensive than most section on disarms. I find his style does not quite lend itself to the rapier I use, having more in common with courtswords and smallswords, which would be my only criticism, otherwise he would be my first preference of source. L’ange’s work is only thrust-fencing, though it includes two-handing of the sword, and multiple disarms and grapples.

Johannes Georgious Bruchius (Late 17th century)

Like L’Ange previously, Bruchius was active on the upper end of the century, perhaps being born a few years after L’ange. The sword depicted in his illustrations looks even more like a smallsword than L’ange’s. I never quite finished Bruchius’ treatise. I got frustrated trying to interpret his Graduren and moved onto other treatises. This seems a shame as Bruchius’ system looks very thorough and complete, and built upon Fabris, Köppe and Thibault. Having lent the work away to a friend, I cannot investigate it much for this summary. He is neither Italian like Fabris, nor German like other authors mentioned so far, but Dutch. His work is titled Grondige Beschryvinge van de Edele ende Ridderlijcke Scherm- ofte Wapen-Konste and was published in 1671. It includes thrust-fencing, and like previously, it has some disarms and two-handing of the sword. Brian Kirk did a comparison of Bruchius with other texts to show how rounded the influences on his treatise are.[2]

Johann Andreas Schmidt (1650-1730)

Firmly in the smallsword era is Johann Andreas Schmidt. Schmidt published his work Leib-beschirmende und Feinden Trotz-bietende Fecht-Kunst in 1713. It appears to have copied from Bruchius (as noted by Reinier van Noort) and Pascha in sections (at least looks that way to me). Schmidt shows how the lineage survived into a much later era, having been still in practice in the 18th century. Technically I believe Reinier van Noort made the argument that this tradition survived all the way up to Siemen–Kahne practicing in 1945. Schmidt took onboard the mission to instruct German youth to be proper gentlemen, a rant Köppe made himself much earlier. For example, Schmidt suggests were you not instructed to defend yourself against a water pitcher correctly, you would humiliate yourself by ducking under a table to avoid it. Schmidt mostly adjusts the system in posture, as it is now a smallsword and he is very much imitating the French and perhaps the English. He includes instruction on Thrust-fencing, Cut-fencing, Vaulting, and grappling (seemingly copied from Nicolaes Petter). Notably he includes an extensive section on Proceeding (Caminiren) and includes two sets of rules to advise on it.

Jonas Thomsen von Wintzleben (18th century)

Von Wintzleben published a treatise in Danish, but appears to be German, and uses German and French terminology. Not much worth adding to this, as much of his work is comparable to Schmidt, indeed it seems largely copied from it, even in regard to the illustrations. A novel thing von Wintzleben does add is a kind of spadroon/cut-fencing section that is not an exact correlate with Schmidt and includes a decent commentary on cross-cutting, though I will confess I am not quite picking up on the significance of what he states. His work was published in Fegte-kunst was published in 1756.

Wilhelm Kreußler and August Fehn

I will not say much on Wilhelm Kreußler and August Fehn. I have no copy of Kreußler’s text, and I have only recently acquired August Fehn’s, and have not read it. I have heard the two texts are linked and that they are their own off-shoot, not easily linked to the tradition that is discussed in this summary.

Fencing Concepts and Swordsmanship:

A lot of these concepts will be principally derived from Köppe. While Köppe is often verbose, he is also often clear. There is very little deviation of concepts, though perhaps Köppe differs a little in his understanding of binding and engaging. Basically, Köppe is the theory heavy weight of the team. Some images are taken from the paper form of books I have, others are taken from Wiktenauer, Brian Kirk’s Elegant Weapon blog, or simply found on a google image search. Merely to save me taking photos on my phone.

Temperament/perspective:

Best handled by Köppe but there is a strong emphasis placed on being aggressive (though not recklessly so). You generally want them to be responding to you, much like Fabris forcing the opponent to act in the first intention so he is prepared to counter whatever action they make. There is a metaphor Köppe uses in regard to Luck, that becomes a commentary on initiative.

“Luck’s forehead is bestowed with hair, but from, her skin is bare.”

Working from memory I believe this metaphor is repeated in Bruchius and L’ange. The message seems to be, you take luck, you make your own luck. To Köppe, tempo and measure are arriving at the right time, and this creates luck. He can grab lady Luck by her fringe, but if she has gone past, she is bald, with no hair to grab.

Working to initiative, at some part of the book, and I have difficulty finding where, Köppe describes meeting an old soldier as a youth, and this soldier saying he had survived so long by essentially playing a game of chicken. He would just advance at them and make his attack the first attack, and the surest attack. Köppe relays that story with humour but it does seem to reflect his thinking on seizing the fight, at least somewhat.

There is plenty of caution advised in the various sources, especially against a cagey opponent, which if I recall, all comment on. So more talk of how to approach the enemy should be in the engagement/binding and camineren (proceeding) sections.

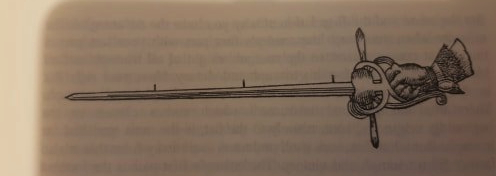

The Sword (schwert):

This is a lineage over hundreds of years, as Reinier van Noort pointed out, it is the longest recorded lineage practiced within Germany. Naturally, this means that various swords were practiced within the Lineage. This includes Rapiers, Smallswords, Spadroons/broadswords (pallasche?). Sometimes rappier is mentioned, sometimes schwert, but more often than not what is referred to is a Degen. Now this can be a stoßdegen, or a hiebdegen, even I believe a hau-rappier. I would not be surprised if somewhere there was a mentioning of Reitschwert but I have not seen it. Degen mostly means sword. Contextually it means duelling sword, and referred to smallswords, courtswords, and rapiers. I believe it was even used to refer to sabres (Säbel). Sometimes within the same treatise there are different weapons, like L’ange has an example sword for dividing the blade, but the swords are greatly stripped down from this in the illustrations, implying they might be training swords. In Pascha the cut-fencing and thrust-fencing appear to have a slightly different sword, but they are very visibly different in Schmidt and von Wintzleben. In those two treatises, the cut-fencing appears to be performed with more of a Spadroon or Pallasch. The principles in these works are universal, but they usually are tailored for a specific purpose. This is why I believe Bruchius and L’ange make better use of a short-bladed weapon, and Köppe and Pascha make better use of a long bladed weapon. They all depend on a complex hilt to an extent, but Fabris, Köppe and H.A.V more so, a similar argument could be made for Schmidt and von Wintzleben in their cut-fencing. The argument being that the hand is more vulnerable when the arm is extended, or when it is at risk of cuts.

My theory on how best to use the sword you have:

Through practice I have come to believe that if you have a short and light blade, it is far better to have a rear-weighted stance, and the arm somewhat retracted in fourth. Then you can make fast attacks, and quick disengages. Meanwhile if you have a long blade that is somewhat heavy, you want to be in Third and extended so you can calmly gain on their blade and switch to Prima (First), Secunda (Second), or Quarta (Fourth) as necessary (as Fabris himself argued). These guards to be explained later, though for the record they correspond mostly with Italian guards, particularly Fabris. Virtually all the authors in this text recommend Quarta (Fourth), with an upright to slight backwards-lean and this explanation is why I think that is so. They also start upright and forward leaning, and gradually move further back in their balance, this is seen as early as Pascha. Köppe and H.A.V would be the key exception, having inherited the Fabris style more strongly, maintaining the extension with a forward lean. Bruchius also tends to have a forward lean as well, though it varies. This makes sense as he plagiarised Köppe and admired Thibault.

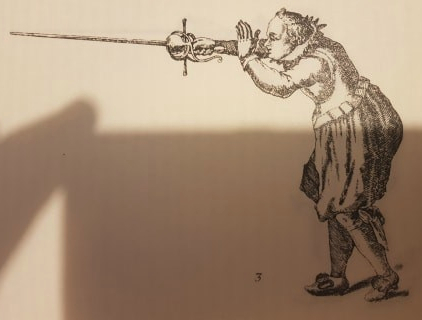

Grips:

The authors do not talk a whole lot about the grips and it can be hard to make out how they are gripping a sword in the illustrations, even when they have deliberately provided a close up and detailed illustration of the hand holding the sword. I believe Köppe recommends a tight grip, while usually it is recommended that they grip the sword lightly. I default to placing a finger around the ricasso (I do not have a German word for this, maybe Starke or One when numbering the swords), though this is not clear in illustrations, only sometimes being visible in say L’ange’s treatise. Köppe with his large pappenheimer style rapier very visibly in the illustration holds the sword below the cross (Kreuz), without wrapping a finger around the cross or ricasso. L’ange sometimes has his thumb on the blade or at least the quillon block. His grip can be described as a smallsword grip, and by extension this is true of von Wintzleben and Schmidt. More often it is stressed to not hold the grip too tightly or rigidly, only firming the grip when necessary such as riposting (versetzen/displace) or delivering a thrust (stoß). This means you are more responsive, and they gain less feedback when gaining your blade. Some of these authors subscribe to Fabris’ theory that you should ideally find or engage their sword without contact.

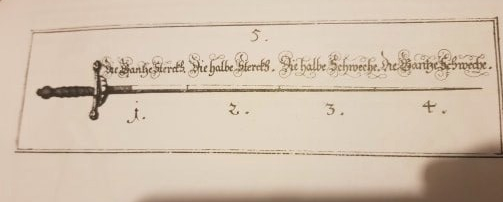

Divisions of the sword:

The sword is divided into three or four parts depending on author, and it should be mentioned they all vary the spelling, including putting e on the end (which usually pluralises a word or changes it into an adjective in German). Köppe divides it into three, Strong (Starke), Middle (Mitte) and Weak (Schweche). This corresponds with Heußler though in practice Heußler will make the odd reference to half-weak (halb-schwech) and half-strong (halb-stark) effectively making it four like some authors. Pascha, Bruchius, L’ange and Schmidt divide the blade into four breaking the middle into half-weak and half-strong. Sometimes the word Gantze/Gantse/Gantsen is used to refer to ‘whole’ or ‘full’ as in fully-weak or whole-weak. The four divisions of the blade correspond to Fabris. As with other authors who divide up the blade, the principle in place is to be able to refer to parts of the blade by use. The stronger parts of the blade subject, the weaker parts are used to thrust or cut. Ideally you have your strong on a weaker part of the blade, often the middle to reduce their capacity to disengage, though like Fabris the ideal is often to have thrust with your hilt coming close to their hilt to completely close out their ability to counter. A word commonly used to describe this is Inteilen (partitioning). Contextually it is like referring to having your stronger part over their weaker part. Like using the word dividing more actively to refer to gaining or graduating on their blade.

L’ange’s division of the sword. Note the difference between it and the swords used in later illustrations.

Köppe’s division of the sword. Note the grip as cited before.

Posture (postura) and stance:

All authors agree that the legs should be somewhat close together, as they all favour a somewhat upright stance. There is a lot of nuance in the differences. Köppe uses multiple latin proverbs and makes fun of people who prance around too upright, and also people who stand with their legs too far apart, accusing them of seeming to sacrifice mobility in favour of looking proud and manly (well before Rock musicians were using the power stance). Most of the authors favour a balanced stance, sometimes with a slight lean back, or a slight lean forward. Often the difference is that Prima (First) is extended with a light lean forward and Quarta (Fourth) is retracted with a slight lean back (though usually more just upright). L’ange and Bruchius I believe point this out for comparison. Bruchius himself seems to have made a compromise between extended and retracted in his stances. I already previously mentioned my theory, so just as a recap, I believe shorter blades favour upright-Quarta and longer blades favour extended Third. Like Bruchius, often there is a middle ground between these extremes in practice. Only Köppe and H.A.V seem wholly committed to a forward lean (like Fabris’ 2nd Book). It could be said all of these are a mellowing of Fabris’ stance. The principles remain the same, mostly upright, feet kept fairly close together so as to make many small steps before making a large step at the right moment. They are all mostly extended in the arm, and they all lunge or pass (passade/passada) into full extension when they strike. All mention deliberate shifting of weight and the counter posture (gegen-postur/contra-postura) though there is also contramotion (counter-motio). For clarity, until Schmidt it is recommended to have your body squared on rather than profiled, there is a process of gradually transitioning to a more profiled stance as the tradition progressed. The logic is that you approach square on and can cover part of your torso with the off-hand, then as you come closer to the opponent you can profile yourself removing one side of your body from threat and achieving maximum extension. Basically, to keep this part of yourself exposed as an invitation until you are actually in distance. In theory you can move faster and more naturally if you are not profiled. Köppe gives the largest explanation of this. Schmidt explains reasons for or against but remains committed to his profiled stance as many fencers had gone by his era.

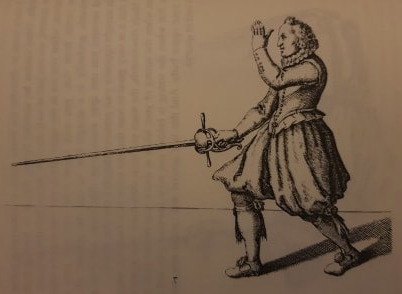

Köppe explains how to get into his posture, it is much like his picture made to demonstrate the openings (depicted later) but you lean forward and take a tiny step forward, while keeping your hands up and in front of your face. One hand holds the rapier, the other is in that position to hand parry. Köppe’s posture is different to most of these authors.

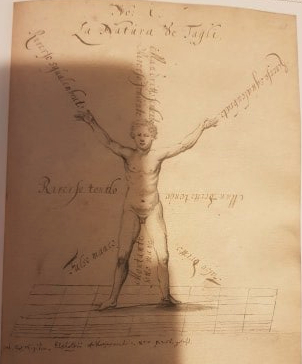

Openings (blössen):

“There is no Art or Science that does not have her certain matter and peculiar profit, and so it is also with this Art and Science. Thus it is then necessary to understand, know, see and acknowledge the openings of your Body and those of your Enemy. Considering these openings, there are three. The first is on the outside, over the right arm, the second is on the inside of the body, to the left breast, the third is below the belt of the pants, to below the hip. For arms or legs are not counted to be openings, because there deadly wounds are rarely or never caused by thrusting. But in a cutting-fight it is very different, for there the head and other limbs cannot be excluded. How subtly these openings must be observed, each can be taught by his master.”-Bruchius

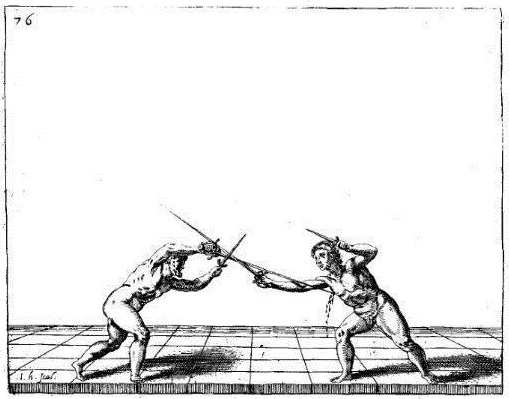

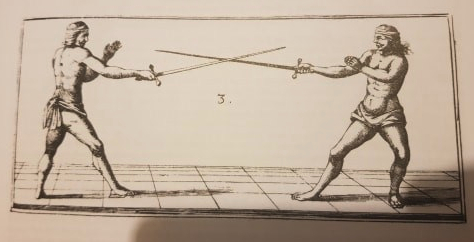

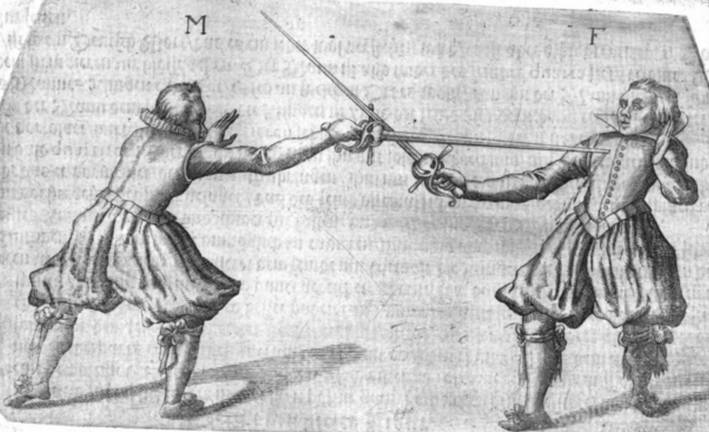

They vary in how they describe the openings but usually their stance is made in consideration of the openings. The arm or limbs are usually only targeted in the cut-fencing, and even then this is a feint (finte) a considerable amount of the time. H.A.V appears to have copied Fabris’ diagram for the openings, and Köppe has done his own version of it. Köppe’s divides the openings into three, basically three divisions of the body, just different heights. His advice is pretty specific. Only target the body, in his region the head was off-target (and I think this might have been true for Fabris?). Köppe explains that the limbs are harder to hit and can be easily moved, not so much the body. The impression you get is to aim your thrusts towards their upper body, through their sword, and in respect to their hand/hilt height. The head being off-target partially explains why some authors like Köppe, H.A.V and Fabris are willing to set it forward while tucking their lower body away. There is also a logic in that their sword and off-hand are at shoulder height to guard the face. Heußler divides the openings into three, and then three again. Essentially upper, middle, and inside and outside for each height.

H.A.V using Fabris’ openings.

Köppe’s openings looking somewhat comical.

Off-hand:

Universally all authors support the off-hand. In the case of L’ange and Schmidt they believe it should always be applied if possible, to allow for a safer attack/thrust. They all give explanations usually riffed from Fabris, though Köppe’s as usual uses a lot more words. This is consistent between them, if the hand is not necessary to support the thrust, then it is at least necessary to cover one of the openings. Referring back to Köppe, there are four real openings, and at any one time one is covered by the hilt, and one is covered by the hand. Bruchius gives an anecdote where he saw someone thrust in the chest, but before it got deep the man grabbed it and pulled it out and went onto win the fight. Often it is mentioned that the hand should be shoulder height, or in front of the face. The hand is mentioned a few times as needing to be very slightly cupped/curved. Köppe suggests a leather glove to protect the hand.

For L’ange, applying the hand is part of a correct thrust. L’ange and Bruchius make extensive use of the hand to compliment their thrusts or responses.

Dagger (Dolch):

Unfortunately, I have not read the books with dagger sections like Heußler. If I was to use a dagger within this tradition, I would either work from Fabris’ use of the dagger (both arms extended, points meeting in the high-middle) or I would merely substitute the dagger for my hand, applying it like a hand-parry.

Example of Fabris using dagger.

Blade-action:

Honestly, too many names are used for engaging and what Italians would call Stringere to name. I admit my memory is pretty faint in this area but I recall Köppe making a dinstinction between two of these (Ligiren and Stringiren), and H.A.V (and perhaps Heußler) uses his own version of ‘finding the sword’ as Fabris would say. I am going to place a commentary below, but I am actually not sure on any of this, except how Köppe has used two of the words (ligiren and Engagiren).

Ligiren (binding) or anbinden (to bind): This is often used to refer to what the Spanish would call tentar or testing. It serves a similar role to a beat. Contact is made at the weak to feel out pressure and openings. This can also be used to move your blade’s point past theirs, as in to cover it or close it out.

Attaquiren (engaging): Sometimes but rarely this is used literally for attack, attaquiren naturally shares a similar meaning. Also shares a meaning with below.

Engagiren (engaging): Basically, make contact with their blade. Usually with contact but who knows, it can be used like Ligiren

Stringiren (to engage): According to Köppe, this means to make contact with your blades, and strike along it with no hesitation. Could call it a hard subject in his language. L’ange and Pascha seem to use it the same way.

Other authors do not always agree. It is often left ambiguous what differences they set between binding, winding and engaging, and the multiple words for engaging do not help. At least Köppe has set a definition.

There are also words for subjecting and suppressing independent of the ones given here, just to confuse matters.

To provide some commentary, I would reconcile both of these terms in practice. If you can engage their blade, gain strength, subject, and thrust, then that is advantageous, but often enough this means they disengage and you’re in the second or third intention. So it is better to leave the process of actually touching their blade until the last moment, basically manoeuvring it until it has already won and cannot be stopped. By the same virtue it is usually good to pre-emptively disengage to seek greater strength, as long as your distance or measure allows. Finally, the usual example of a good thrust is given through the example of a straightforward engage and lunge.

Measure (Mensura):

Köppe uses Measure to refer to how strong you are on their blade. I do not think this is common outside of him, though in practice with the association of time (tempo) and distance it does not really matter. I will explain the Italian use of the words, which is a lot more common even in the German tradition.

Long measure (Mensura Larga): Distance where you can hit them with a step.

Narrow measure (Mensura Stricta): Distance where you can hit them without a step, like a lean or full extension of the arm.

Out of measure: This is not really mentioned but Köppe does have a few rants about people who never want to come into measure. He usually thinks they are cowards, and that they should eventually lose if they keep retreating. Personally, I am inclined to agree that there is no value in sitting out of measure, it just stalls the fight, and you will not always have the room to evade. I also often can punish someone for perpetually retreating. A retreating offers a tempo if they have gradually lost their distancing.

Motion (Motio):

There is much said on movement. It is given large attention in virtually every work. Köppe as usual has the most to say. I do not want to do it a disservice by saying too much here. it is much like Fabris’ idea of movement (not quite his rules of resolution though). You are upright, and already extended, so you take small steps, moving with your feet more than the rest of your body, then as expected, when you are in an advantageous position you extend, with a lunge, or passing step. They do not seem to favour offline or linear but instead are about using whatever step suits the action, whatever step you need to go under, or over their blade with your thrust. It should be mentioned, Pascha sees the time the enemy is stepping (particularly big steps) as the best moment to strike, for they are not firm-footed or balanced if one or more feet are off the ground. Pascha has half-thrusts (and I think Schmidt does too), and these are sometimes sold with a small movement or step, either a lean or tiny ‘gaining’ step (to borrow a term from others). Köppe strongly emphasises small motions with hand or feet. The impression you get is that the German authors want to make small non-committal motions and only make big actions when it is ideal. If they need to advance straight and under the blade, or offline and over the blade so be it.

Three styles of fencing:

Pede firmo, Passada and Camineren are all given attention by the masters though it varies how much, and the explanations vary somewhat. All three do seem to be considered essential to the practice.

Pede Firmo (firm-footed): Pede Firmo is the subject of Fabris’ first book, basically fairly upright, foot-planted and making lunge and recover kind of actions. This is considered pretty typical and standard of Italian Rapier of the time. Fabris considered this the fundamental style of play before he sells you on his second book with proceeding where these kinds of fundamentals are performed on the fly with a different kind of step. Pede–firmo is the predominate style of fencing in the German tradition, and normally what they introduce first though they give strong attention to passing, and varying levels of attention to proceeding. For example, L’ange is mostly pede firmo and has some passade and only gives a page to proceeding. Meanwhile Pascha is probably 5/10 pede firmo, 3/10 passada and 2/10 proceeding in ratio.

Passada/Passade (passing): This is often used to mean stepping, without a lunge, more then it is used with a clear purpose. Occasionally it is used to describe a step where the rear leg passes the front, but most commonly it is stepping offline with your right or left leg (as opposed to a lunge). This is hyped up to varying degrees. The passada is often highly revered as a form of fencing and movement. Sometimes the passada and caminiren are linked in that you are advised to simply take small steps until you can make an attack with the passada safely.

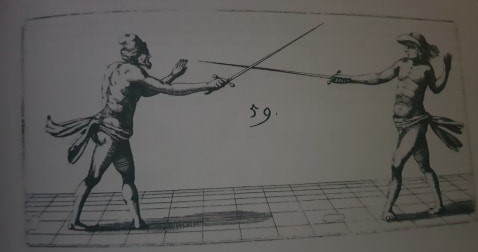

Caminiren (proceeding): Often this is talked up but less unexplained, or quickly dismissed as something that is merely passada with shorter steps. Köppe gives a fairly lengthy section but does not manage to say a huge amount. Obviously, this comes from Fabris’ ‘proceeding with resolution’ (Resolution actually is literally spelt that way in these books too). L’ange is the curtest about caminiren, giving it only a page and saying it is so vain it must have been invented by a Spaniard. He also suggests that it is good for old fencers and retired soldiers who have bad legs. Pascha adds caminiren variants for his earlier plays. Schmidt of all people, and well into the smallsword period adds multiple rules to caminiren, far more than Fabris did.

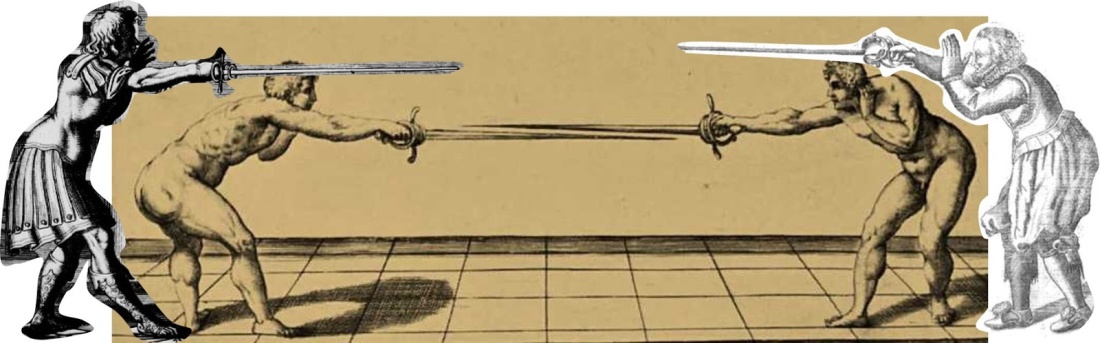

To expand on Caminiren it is a type of walking fencing. By moving naturally as if you were stepping you can gain ground with little risk. Since you are using uncommitted steps, and keeping your arm extended, you can move into threaten someone so they are provoked into attacking, but as you instigated this, you can then act in the second intention to thrust and as you did it by proceeding and are already in a good position and posture, you can essentially thrust in ways you would not get away with otherwise. The hardest difficulty I have with this is getting low enough. As seen in Fabris’ illustrations, and argued convincingly by the fencer and blogger Brian Kirk, Fabris keeps his arm mostly aligned with his shoulder height and would lower himself until his arm was at his opponent’s hilt height[3]. This is awfully awkward for someone tall or who has not conditioned their leg and back to this (and hip-hinging only alleviates so much). It does seem to be the physically most efficient way to shut out their attack and advance on someone safely.

L’ange emphasising the casualness of caminiren

The Disengages:

These form a big part of the swordplay. Though they are simple to explain or summarise, they are often given their own plays, and variations depending on footwork, such as the default (pede firmo) or passing (passade) or proceeding (caminiren). The counter to a disengage is both a counter-disengage (cocaviren) or to interrupt it by moving your blade into Secunda (Second) or Quarta (Fourth). The play setting up the last sentence is usually starting with a thrust in Third.

Disengage (caviren, durchgehen) or disengagement (cavation):

To go under their blade.

Reverting:

To go over their blade.

Re-disengage (re–caviren):

To go to disengage and then cancel it (go back to where you were)

Counter-disengage (cocaviren) or counter-disengagement (concavation):

As the disengage, you disengage.

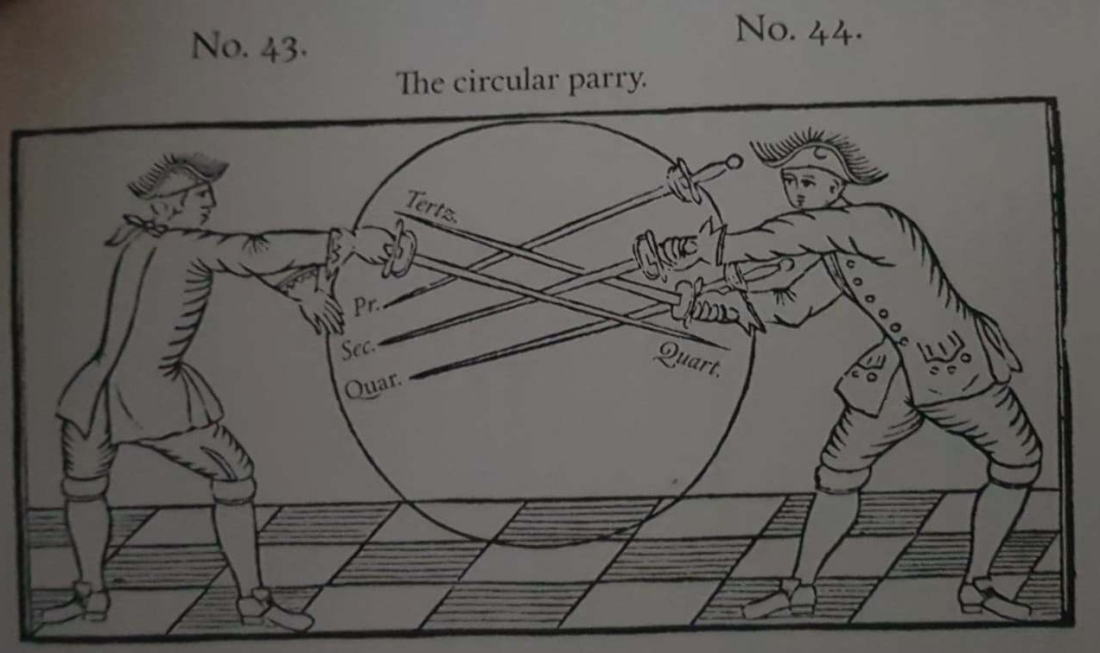

Circling (circuliren):

This is when you circle their sword, either to gain measure (strength) or to break it (like a retreating motion). Corresponds to the fencing term envelopment.

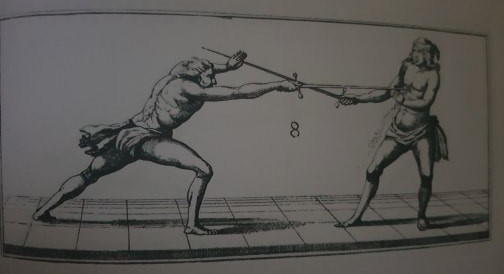

Voltiren (turning):

Like Fabris’ Girata the German authors make use of various degrees of turning. The most common being when you step with your non-dominant leg around to void your body, usually with a thrust of Quarta (fourth) and often against a thrust of Quarta. Sometimes this is called the false step (as it steps with the non-dominant leg, sometimes even forwards rather than merely offline). Fabris’ other giratas might be referred to as voltiren, or they may be referred to as another example of passade.

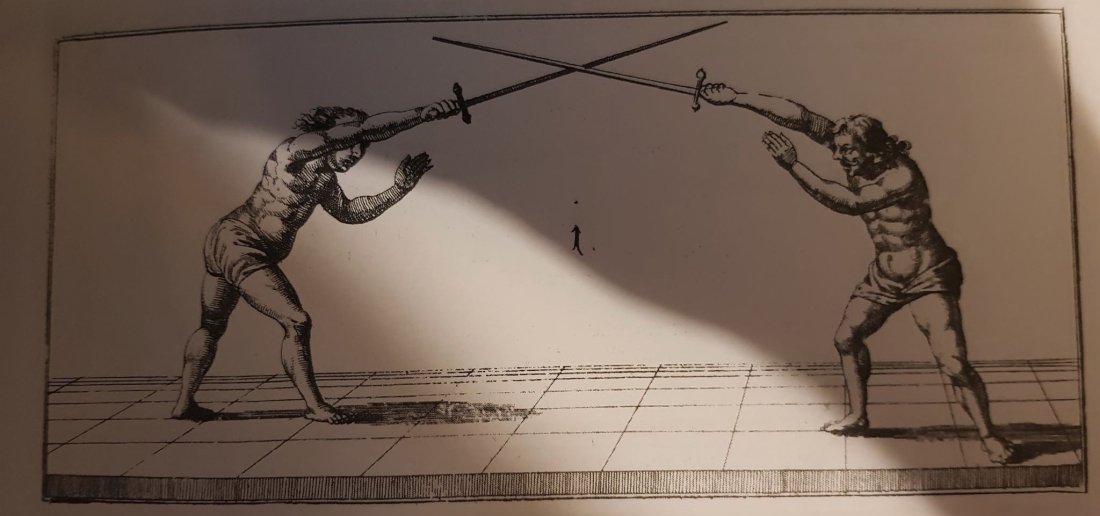

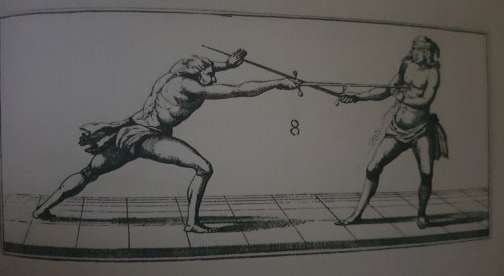

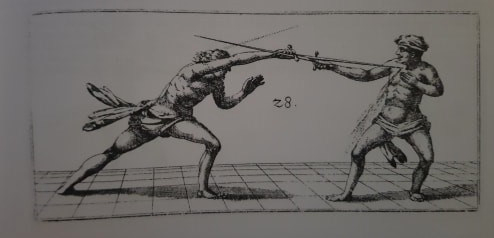

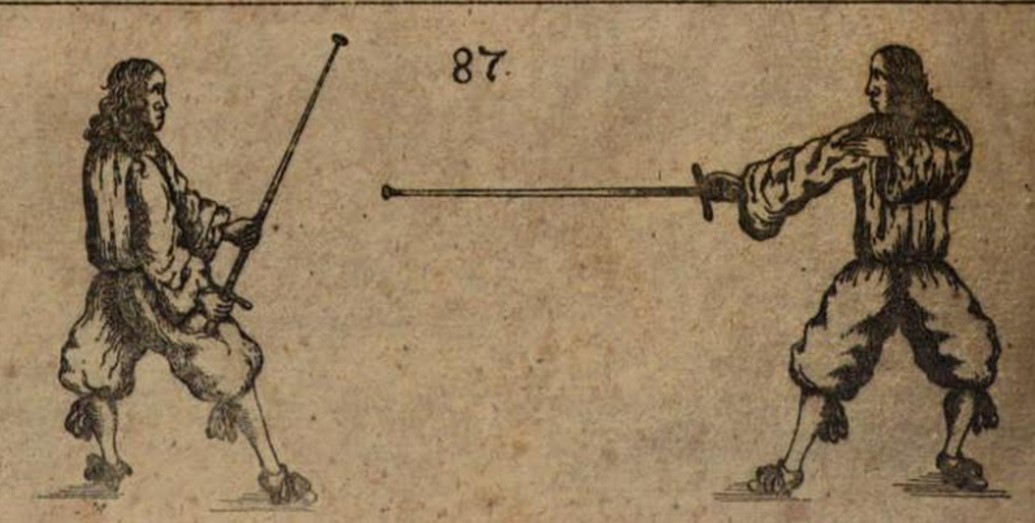

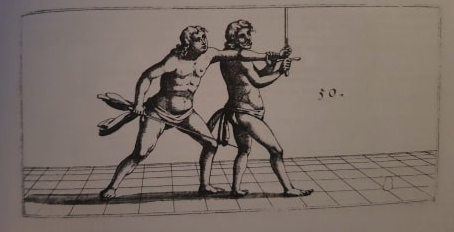

Pascha performing a voltire to counter another.

Feinting (Fitiren, verführen):

Most of the authors give rules for feinting. Köppe and

Schmidt’s are quite extensive, I have not checked but I believe this is often the case. My

favourite would be Pascha’s use of a ‘half-thrusts (halbe-stoß). This is to perform feints by thrusting only with the rear foot moving closer to the thrust foot so you are not all in on your feint though obviously prepared to extend it.

Withdrawal:

Explained in multiple places but very succinctly explained by Heußler as stepping back slightly with the left foot, so you can void an attack. This is much like the Spanish Balanzada (and Quibro) and almost matches Godinho’s description of those actions.

Battire (used by Heußler and others) and Appel (used by Schmidt and others):

Used to refer to a beat, or a stomp of the right foot and usually both. The implication is that an association is built between them making it into an effective feint. My personal experience is that this association needs to be built and does not work if that kind of trigger has not been set. Fabris and others would hate the idea of giving someone a tempo by doing an action like this, I believe it does not mesh with all the authors in the tradition.

Guards/postures:

According to Köppe there are no guards, and the translation for the Italian Postura should be Stellung (position). Lager, Garnison and Guardi to him are useless unless referring to First (Prima), which is the only time you are waiting or at rest, having just drawn it. Having said that, the others are not so pedantic about this distinction. It is totally acceptable to use any of the words he just described. Guard or Posture both work fine for a English translation.

The guards are often translated into different forms for example Prime or Prima, Secunda or Seconde. Those differences are not that different within German pronunciation but there is also differences such as Tertia and Tertie which are less similar. For convenience I have again gone with the Köppe spelling for preference/convenience, that is Prima (though he also uses Prime), Secunda, Tertia and Quarta.

As others would note the guards correspond to the convention seen in contemporary Italian sources. They often describe them by where the knuckles, thumb or palm is facing. This means we end up with high and low Secunda and low Tertia and variations like that, who are named such for their hand position rather than their height or extension. It would be too much to show every variation of the guard, so I have picked a few by their relevancy, or novelty.

Fabris showing a poor Tertia

Köppe is not as negative of it though it is not his preferred Tertia and he does criticise it.

Fabris’ Tertia being compared with Köppe’s Tertia and Thibault’s portrayal of Fabris’ Tertia. Image like some others taken from Brian Kirk’s blog.[4]

Köppe’s preferred tertia like seen above.

Bruchius and Pascha’s Tertia. Pascha does a more extreme Tertia as a parry too.

Example of L’ange’s Secunda (left) and Quarta (right).

Pascha’s low Secunda, used to parry a low attack or address a lowered sword.

L’ange’s high secunda.

Bastards (Bastarde): Just as Fabris used the word bastard to describe a guard between two guards, so do most of the authors presented here. They are not mentioned too often, it seems to be assumed you find yourself in these positions naturally in motion between them. Notably Schmidt considers the left bastard (between Quarta and Tertia) the best hand position.

Thrust-fencing:

It would be too much to explain all there is to Thrust fencing. It makes up the bulk of their commentary, all their principles are made to inform on it. The plays/variations/exercises are easily in the hundreds, even if you don’t count the ones that are the same between authors.

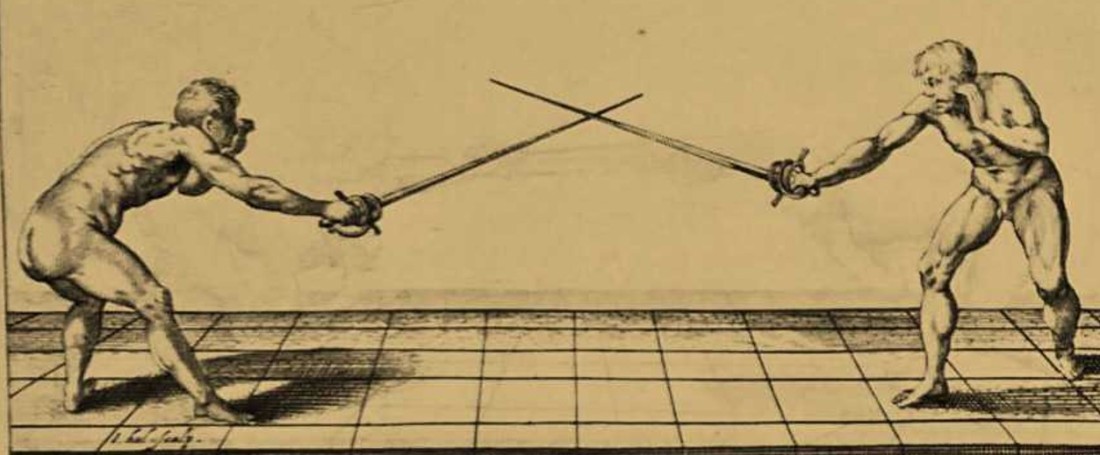

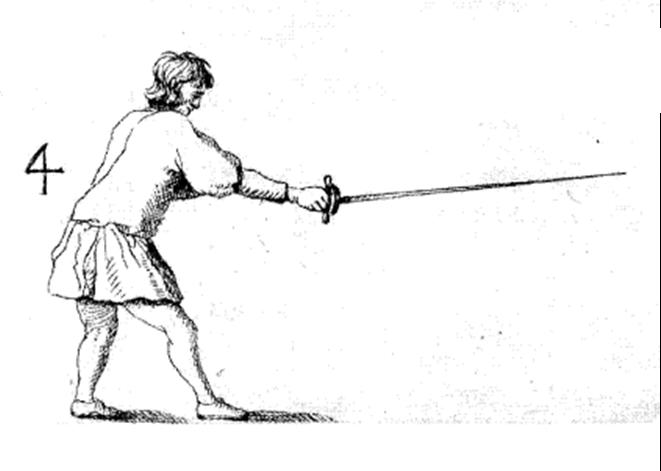

The thrusts are all named after the hand position (Prima, Secunda, Tertia, Quarta). Initially the examples given tend to be straight forward, engage their sword (with contact) and thrust on the inside or outside, which ever has the true edge against their sword. Sometimes hand parries are added into this, particularly in the case of L’ange, Bruchius and Schmidt. All the repertoire mentioned before is usually added in, such as passada, voltiren, and caviren. A common enough play is to thrust and be driven up and then pass or void low to deliver a thrust now their weapon is committed up and outside of you.

As the authors will often say, the thrusts are delivered above and below the arm. Usually an attack made over the arm is done with a lunge and below with a passada but this is far from always the case. Some like Schmidt recommend thrusting under the sword (like in Prima or Secunda) for shorter fencers and point out that all other actions are easier for someone taller. I suspect if you managed to memorise every play and did a complete reading you would find insight into what distance and footwork you need to counter every situation or engagement. Being in the right distance or responding with the right footwork are far more important than hand position or height of the sword.

Some general advice provided by virtually all the authors included here is that you look to where their blade is and their openings. This is the advice Fabris originally gave as well. An example is if their point aims towards their left, you attack at their right. It echoes the principle of strong and weak and partitioning the blade. How they compose themselves will leave openings and mean the weak of their blade is in another place. You are aiming to target the weak in a way that you can gain strength and close off their retaliation. All these factors are what informs you whether you thrust over or under the arm.

Changing the hand position can be used to gain strength or curve around or disengage. Feints can be made high, low, left or right, with or without a step. Parries can be made high, low, or middle. A riposte is often considered more virtuous than a parry.

As mentioned before some prefer hand-parrying more than others, but it is often employed to reinforce a thrust or to parry an attack (so you can thrust safely in the same time). Hand parries and voiding, sometimes together, are very important parts of the system.

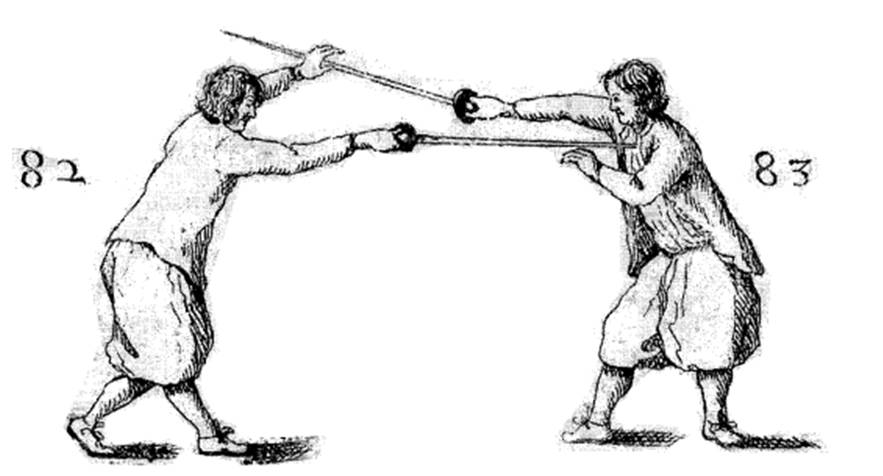

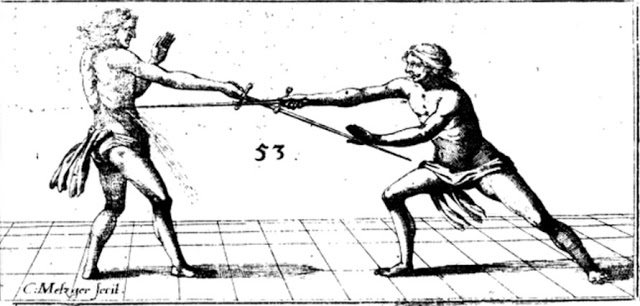

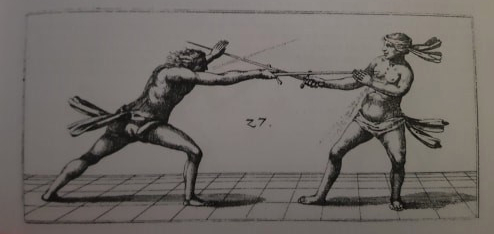

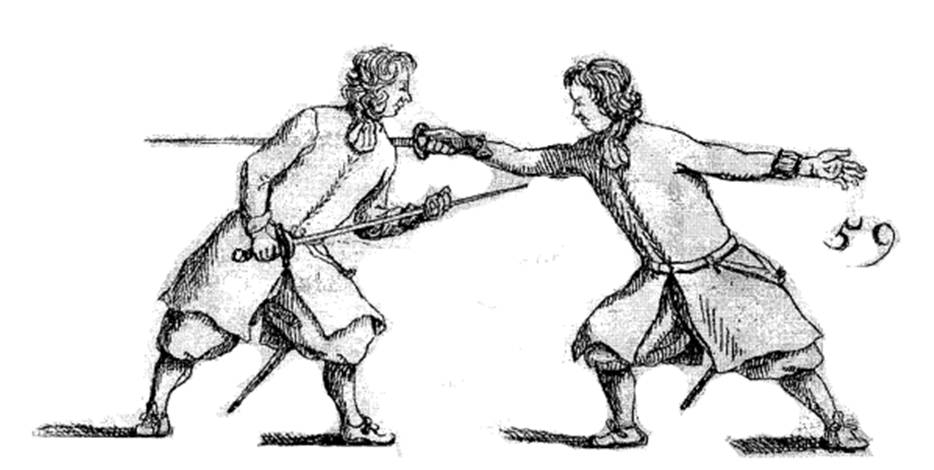

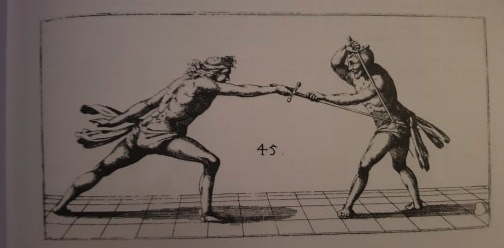

Often the illustrations of the blade and quillons are deceiving. L’ange is thrusting with Tertia and Pascha is thrusting in Quarta.

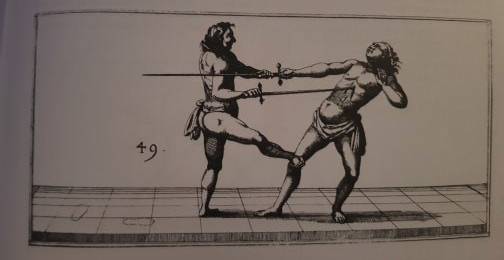

Pascha delivering a thrust of Quarta.

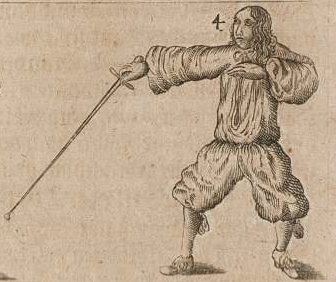

Köppe delivering a thrust of Tertia with opposition, note his hand is not applied but remains reserved for use.

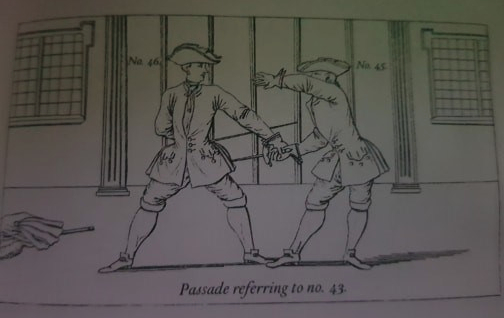

L’ange demonstrating the correct thrust of Quarta using the left hand for further safety.

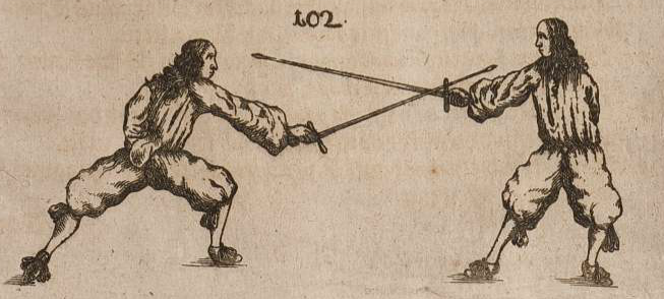

A very similar action from Bruchius.

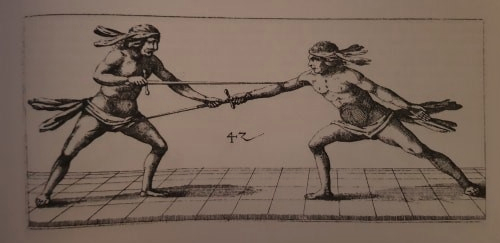

L’ange calls this the quarta under the arm. It resembles the flanconade which appears in multiple sources, almost certainly being taken from the French (as sometimes they will themselves will cite).

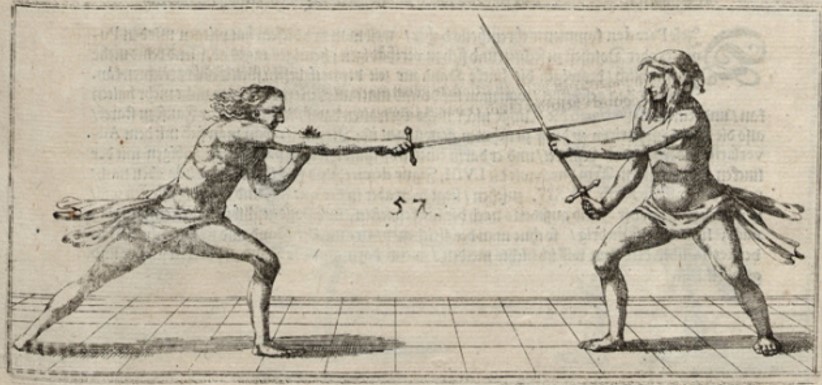

L’ange demonstrates the gliding thrust. Showing where they start and where they finish.

Another example of the gliding thrust this time going over and in second.

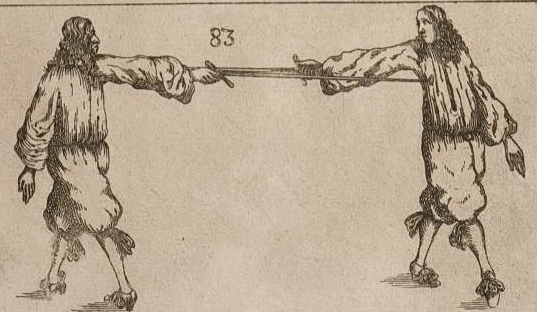

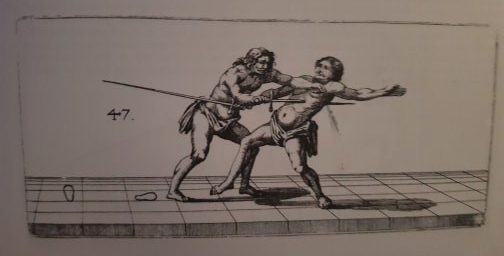

Two-handing:

Like other rapier treatises these authors have instances where they two-hand their sword or half-sword. It seems to be an unsubstantiated myth that these kind of actions do not exist in rapier treatises. I started with Fabris and this treatise so I too thought there was some novelty to two-handing the sword but Brian Kirk demonstrated pretty conclusively that these actions appeared in other treatises.[5] Fabris used it to compete with the strength of a spear, and I believe Figueyredo in his dagger section recommends half-swording the sword to compete with the nimbleness and strength of a dagger. The explanation found in the German treatises seems to be if you are tired, so you can parry quickly and strongly this way. In practice I have found it is an excellent position to kind of fling or sling the sword from (which are actions the sources condemn). It becomes deceptively long range, much the same reasoning that justifies one-handed thrusts with two-handed swords in the Italian treatises. The use can sometimes resemble Thibault, such as Bruchius emulating Thibault’s Torneada (Tornado).

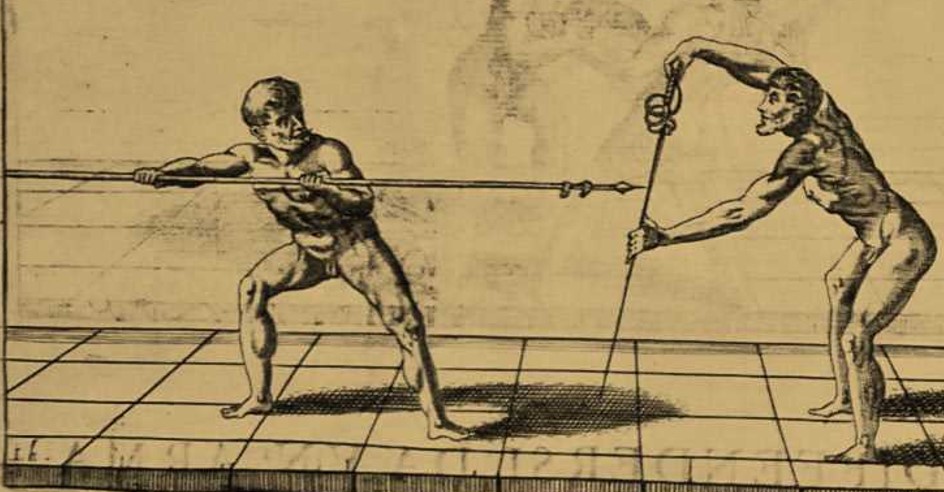

Fabris two-handing his sword to compete with a polearm.

Bruchius two-handing his sword after being past their point.

L’ange blocking with two-hands

Pascha two-handing his sword.

Disarmiren(Disarm):

Virtually all the authors feature some form of disarming action. Often this is simply just to deflect with the hand. Sometimes it is to grab the hilt and work from there to secure a thrust, even pivoting and pulling much like you can see in other traditions (Spanish comes to mind, and relatedly Thibault). Sometimes they can be quite forceful which is uncharacteristic for rapier treatises. Some treatises are accompanied by grappling sections so it makes sense that they would integrate this knowledge into their fencing. L’ange seems to view his fencing as a system of self-defence rather than for duelling. He is not the only to say this, but maybe the most explicit. Extension of this he has a section on dirty fighting but also many disarming actions that appear quite brutal such as breaking the arm or knee. It seems just as L’ange has advice on drawing your weapon in an ambush, or moving your opponent into the sun, he also has advice on disabling them if you and your opponent end up too close. For a good example of what other authors like Pascha have to author check out David Coblentz Pascha Part 5[6] and 6[7] videos have some of Pascha’s disarms, though to me they seem a little altered.

Two examples of L’ange breaking measure, first like the Spanish ripping or breaking (called Rompeiren in German). Second is like a conclusion having pulled their weapon after they are committed and over-extended.

L’ange also has instances where he goes for a throw, before or after thrusting them. The trip/throw working for added safety.

Not too often seen in treatises, L’ange is willing to break the arm or leg.

Schmidt’s passade look like disarms such as this one which resembles an action seen in Joachim Meyer as Robert Rutherfoord has dubbed the hidden stucke (hidden thrusts).[8]

Dirty fighting:

Sometimes you will find the odd recommendation to what could only be described as fighting dirty, or on the street. Köppe refers to what you should do when ambushed or attacked. For many of the authors the selection of the sword factors in the ability to draw it in the case you need to use it for defence (not just a duelling environment). This is discussed in regard to ideal length though they usually do not give specifics but generalisations such as not too long to draw or carry. L’ange talks about picking your location if you are to fight with sharps. This includes advice such as moving your opponent so the sun is in their eyes, or driving them up a hill. This seems related to the use of grappling, and other tricks (two-handing the sword). There is an idea that what they teach is not just an art for a fencing school or to resolve disputes but a means to defend yourself.

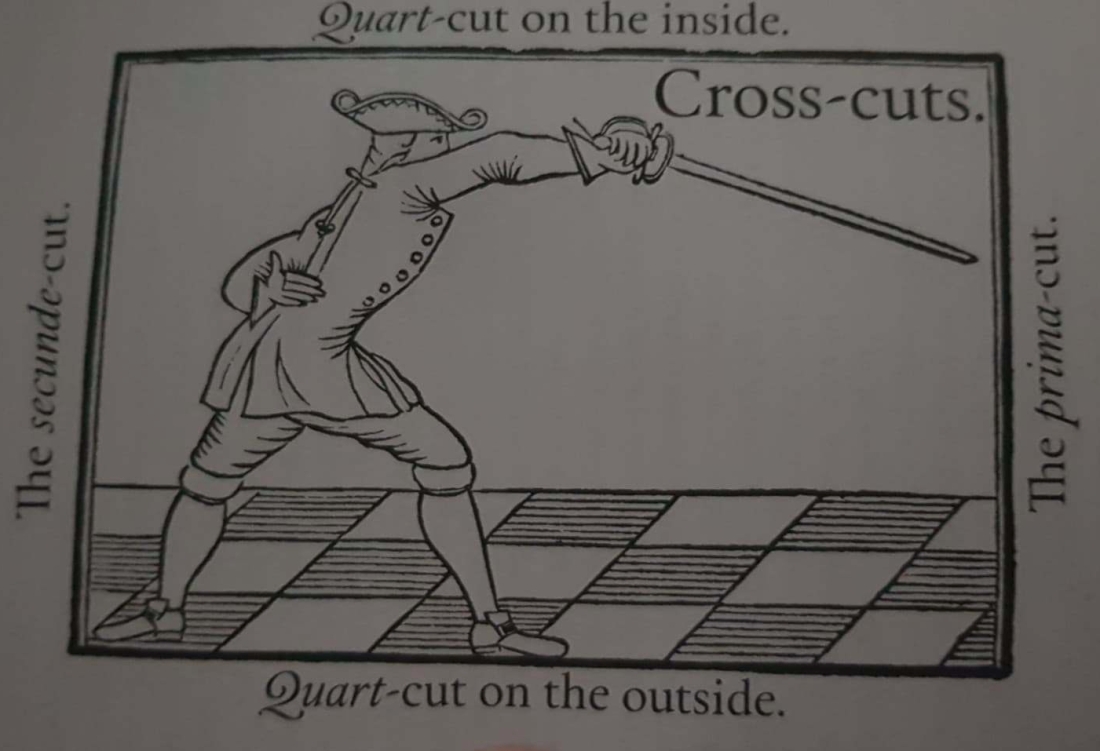

Cut-fencing (hieb–fechten):

Fabris speaks really briefly on cuts and for the most part this is true of the German authors. They may offer some words on what the cuts are named. They may say how best to cut. They may have a few token examples of cuts (such as L’ange and Bruchius doing the cut with a rumpieren). Still, for the most part their fencing does not feature cuts. Curiously, authors such as Pascha, Schmidt and von Wintzleben dedicate sections to cut-fencing, and honestly they do seem derived from Pascha’s version. Since Schmidt and von Wintzleben wrote in an era where there was sabres, broadswords, pallasch’s and spadroons (and however else you would refer these weapons) it is less unusual that they would include these sections, making Pascha look the odd one out. The weapons in these sections look different to the thrust-optimised weapons in their cut section, though it is really hard to tell if Pascha is depicting a separate weapon, the weapons seem by Schmidt and von Wintzleben are clearly different resembling spadroons or pallasch. August Fehn of Kreußler’s tradition has a section on the Pallasch too.

Pascha changes his posture placing his left hand behind his back and stretching out the right hand more (since his guard was a little less outstretched than the other authors to begin with). The language for his cuts are similar to the guards in his thrust-fencing, that is where the hand position is after completing the cut is what the guard is named. So his cut of second is from left to right ending up with the palm down. For cutting he favours the guard of Tertie (Tertia). Most of the cut fencing is simple parry and riposte, and sequences with feints added in. I am unsure if his false cuts are a result of coming at an odd angle (such as below) or are explicitly with the false edge.

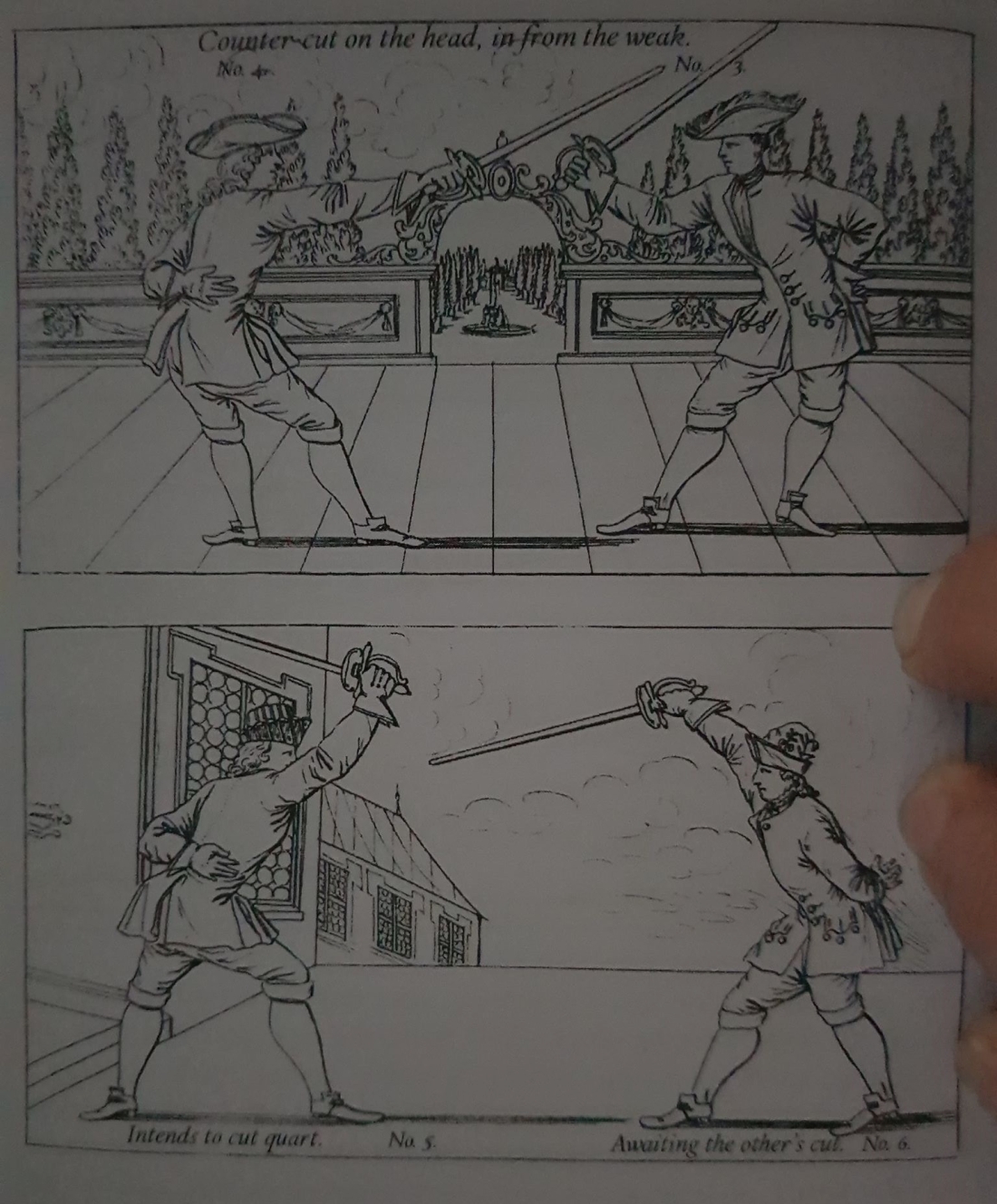

Pascha parrying a cut of quarta.

Schmidt’s manual reads fairly similar in the introduction, he reminds the reader that the cuts are termed like in thrust-fencing and that what has been covered can be applied to the cut-fencing (which echoes Pascha’s introduction). He has made the system perhaps more efficient and similar to conventional cut fencing of his time by moving towards a default hanging posture. Schmidt has less exercises than Pascha but the actions within them seem much less repetitive, and more specialised. Schmidt’s treatise reads more like a military treatise, like the formal cut-fencing of the time. It feels like he covers more ground than Pascha’s broad actions and repetitive sequences.

Examples of Schmidt’s cut-fencing. Format appears to be assigning a cut to one party, and a counter to the other.

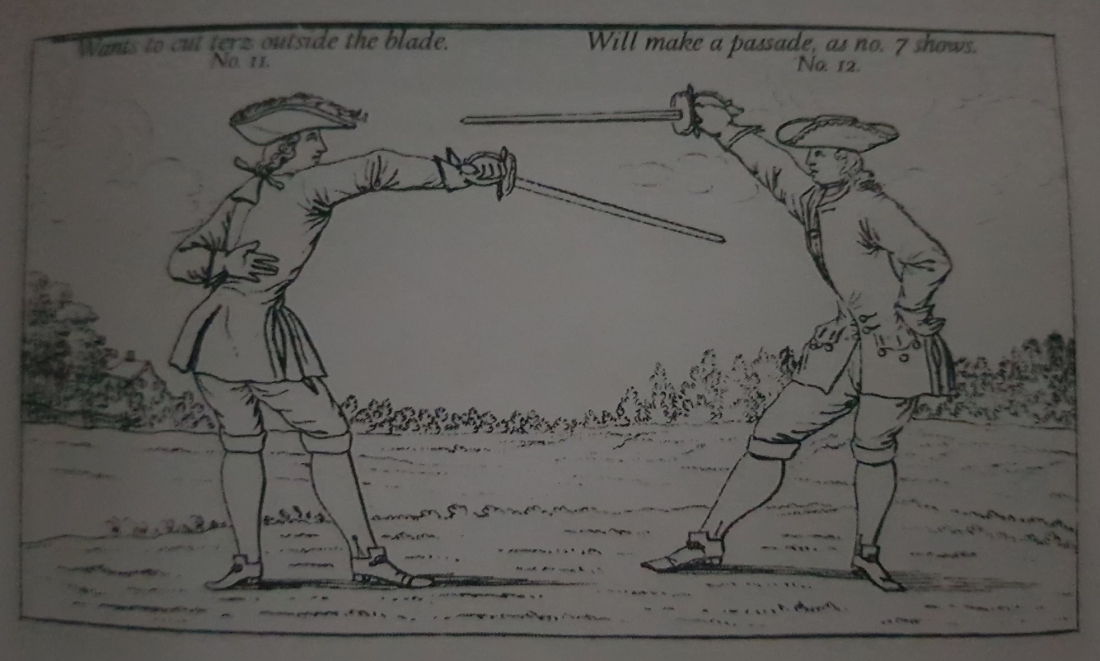

Von Wintzleben offers less than Schmidt, and as noted previously appears to have copied Schmidt. He has a nearly identical image to what is presented just above. In his cut section he appears to offer general advice and rules more than the specific actions or plays Schmidt has a wealth of. Von Wintzleben does give special attention to circular parries (at least a late image of such) and cross-cutting. Though I am unable to derive any special insight to his cross-cutting compared to the general definition and utility of a cross cut having close the line.

Von Wintzleben demonstrating circular parries and cross cuts. Note the similarity to Schmidt’s illustrations.

It should be noted that all the cut-fencing sections start to target arm, limb and head more than the torso, which is the de facto primary target of the tradition.

Advice both to myself and others on practicing this system:

Look to Köppe for the theory. Look to L’ange for a short easy summary (and some interesting grappling). Look to Pascha for structure (and if you want to cut with sidesword-like rapiers). Look to Bruchius for a more complete understanding.

Also Heußler appears to be a good introduction especially if you are fencing more with sideswords.

If your focus is on smallsword you should definitely be reading Schmidt, especially if you want to transition from an Italian Rapier system into Smallsword (so you do not have to learn the French/English conventions).

Conclusion:

The German tradition imported what they considered to be of best utility and applied it pragmatically, writing these lessons down in a very well-structured format. This offers the German tradition a versatility not often seen in fencing traditions as they have encountered many influences and formulated responses to such. This summary has only applied to single sword with some mention of dagger, but the authors also covered other weapons as mentioned in the Authors section, such as partisan or grappling. As Reinier van Noort noted, this is the longest recorded German fencing lineage, if drawing a line from Fabris to Siemen-Kahne.[9] Having been practicing this style of fencing for some time, I feel like it is nearly as streamlined as the Neopolitan fencing tradition, and probably a bit more robust. I think in the future a better summary could be provided. One that aims to identify each action as it appears (how much it appears) and so give a more complete overview of this tradition.

[1] Noort, R., & Schäfer, J. (2017). An analysis and comparison of two German thrust-fencing manuscripts, Acta Periodica Duellatorum, 5(1), 63-74. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/apd-2017-0002

[2] https://elegant-weapon.blogspot.com/2019/06/episode-164-elements-of-other-systems.html?q=Fabris

[3] https://elegant-weapon.blogspot.com/2019/05/episode-163-some-observations-on.html?q=Fabris

[4] https://elegant-weapon.blogspot.com/2019/06/episode-164-elements-of-other-systems.html?q=Bruchius

[5] https://elegant-weapon.blogspot.com/2018/08/episode-147-holding-rapier-with-both.html?q=bruchius

[6] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIOcn_KupwQ&t=221s

[7] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ijY33xHp2lo